Water may split state into 'haves,' 'have-nots'

Water may split state into 'haves,' 'have-nots'

[From the Oregonian's coverage of the latest IPCC report on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability:]

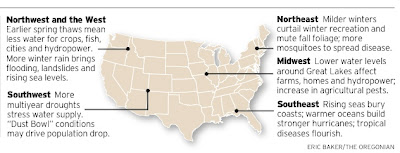

The Pacific Northwest faces an intense tug of war over vanishing water supplies if the region continues to warm as forecasts show, dividing people west of the Cascades from those east as water "haves" and "have-nots." And even abundant water west of the Cascades may be stretched as people fleeing from drier, hotter regions of the U.S. find refuge here.

Scientists base this warning on findings to be released today in Brussels, Belgium, by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a consortium of more than 2,000 climate scientists from 130 countries.

Among other things, the American Southwest will face dust bowl conditions as hotter temperatures rob as much as 20 percent of annual rain. But in the Northwest, dwindling mountain snowpack is expected to make summer water scarce especially east of the Cascades, challenging agriculture, river use and human habitation.  [Image: Projected climate change impacts in the United States]

[Image: Projected climate change impacts in the United States]

Devastating wildfires throughout the West are expected to increase. And sea levels will rise everywhere, in Oregon and Washington eroding and undermining the rugged coastline. These scenarios are coupled, strangely, by extreme winter rainstorms, particularly west of the Cascades.

The scientists assess the potential impacts of global warming in a summary today of "Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability," a 1,500-page report to be released later by the organization, set up in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Program.

Scientists interviewed by The Oregonian who have seen drafts of parts of the report agree that for the Northwest, snowpack, which holds two-thirds of the region's stored water, poses the most serious problem.

The slow melting of snowpack through the long summer months is vital: It fills rivers, driving hydropower, irrigation, salmon runs, recreation and expanding cities. But snowpack has been shrinking in recent decades and is expected to continue its decline.

Worse, warmer winter temperatures cause earlier snowmelt in the spring, "so you can expect to have both an increase in flooding and an increase in drought in the same year," said Edward Miles, a researcher with the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington. Earlier snowmelt means lower summer river flows at a time of peak demand, especially in the irrigation-dependent eastern portions of Oregon and Washington.

"We now have the basis for social conflict in which the difference between the haves and have-nots grows much wider," Miles said. "People on the east side will be the have-nots in this case."

Similar conflicts and declines could occur throughout the world, the scientists familiar with the report say:

Coral reefs and other marine systems likely are suffering from higher temperatures and shifting ocean chemistry, and coral will probably enter a major decline.

Satellite evidence shows a trend of plants and trees greening earlier in the year as higher temperatures expand growing seasons and extra carbon dioxide feeds plants. But that may not continue as higher temperatures also have a drying effect.

About one-third of the world's plant and animal species will either move from their present range or vanish.

Rising sea levels will drive millions of people inland from flooded coastal and low-lying regions, particularly in heavily populated coastal areas in China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia. U.S. coastal wetlands and low-lying areas of the Southeast and Northeast could be hit hard.

By 2020, between 400 million and 1.7 billion people worldwide will not get enough water.

The bleakness of the findings today are underscored by a February Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report that stated people "very likely" have played a role in global warming.

Managing water

Determining how to best allocate limited water resources is the main challenge facing the Northwest, said Michael Scott, a natural resources economist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Wash., who co-authored a draft of the report's North American chapter.

Although he declined to give details about the report before its release today, Scott said the ongoing struggle about how best to manage water "certainly will get no better and maybe worse."

Steven Running, a professor of ecology at the University of Montana and also a co-author of the draft North American chapter, said northern latitudes from about Portland north into Canada would see longer agricultural growing seasons.

"Areas that are not water-limited that get enough natural rainfall will do better," Running said, "but areas that have this longer growing season but get less rainfall could be in real trouble. For example, as you go off into eastern Oregon and are really out in the desert, the last thing they need is more heat and less water."

Western wildfires are expected to accelerate. A recent study found that higher temperatures and earlier spring snowmelt caused a dramatic surge in large wildfires across the Western United States in the past two decades.

"There's no reason to be optimistic that the wildfire frequency is going to do anything but become more regular," Running said.

Although coastal residents might escape high temperatures, they will face the prospect of a sea-level rise caused by global warming. Oregon and Washington's beaches and low-lying communities would be more vulnerable to erosion from storm surges and high tides.

Societal issues

The social issues presented by global warming -- such as the conflict between those who will have water and those who won't -- are gaining the attention of climate specialists in Oregon and Washington.

"We expect more contention over water resources much like what we have seen in the Klamath Basin," said Mark Abbott, co-chair of the Governor's Climate Change Integration Group, which is examining what steps Oregon can take to prepare for a warming climate.

Abbott, the dean of the College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University, said many people are concerned about a large migration of people into Oregon from areas that will be more heavily affected by climate change, such as the U.S. Southwest. Other questions include whether there will be "disproportionate impacts" on human health, such as more heat-related deaths and higher electricity costs among the elderly.

Eban Goodstein, an economics professor at Lewis & Clark College who is studying global warming's economic impacts, anticipates that migration into the region from cities such as Los Angeles and Phoenix will accelerate. "They're unsustainable communities right now in terms of their water supplies. And as temperatures warm up, I would imagine we would see more and more in-migration driven by climate," he said.

"In the Northwest, we're going to see snowpack loss leading to water shortages, an increase in catastrophic forest fires and sea-level rise as the dominant impacts," Goodstein said.

"We need to prepare. It's going to be a rough century."

After reading the dire reports on global climate change’s potential impacts on our state and our planet, I am comforted by one thing: we can still avoid this bleak future.

Despite the fact the world’s scientific community has come together to issue a remarkable consensus report detailing a future drastically altered by climate change, I still have hope that we can avoid this future – if we act now!

Luckily, Congress is considering legislation right now that could prevent such a bleak future for Oregon and the world. Comprehensive, science-based climate change legislation introduced by Congressman Henry Waxman (D-CA) in the House and Senators Bernard Sanders (I-VT) and Barbara Boxer (D-CA) in the Senate will put the United States on a path to rein in our global warming pollution and avoid the scary future described in the latest IPCC Report.

Scientists tell us we need to cut our global warming pollution by 80% by 2050 in order to avoid the worst affects of climate change. Of all the proposals before Congress this year, only the bills sponsored by Waxman and Sanders/Boxer get the job done.

We still have time to avoid the dark future described in Friday’s article, but time is running out. We need to enact comprehensive, science-based global warming legislation now and get our country on a path to a sustainable energy future. We simply can’t afford to not get this right!

[Image credits: The Oregonian]

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

News From My Backyard: Global Warming May Split Oregon In Two

Posted by

Jesse Jenkins

Ads at www.WattHead.org:

Wind Turbine Training

Solar Panels and Kits for the Home

Solar Energy Products and Home Solar Panels

Wind Turbine Training

Solar Panels and Kits for the Home

Solar Energy Products and Home Solar Panels

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment